[ad_1]

A moment ago in “Stan Lee”, David Gelb’s vivid and illuminating documentary about the Marvel Comics visionary, is important enough to give you chills. It’s 1961 and Lee, nearing his forties, is exhausted from comic books. It’s a form he’s never taken seriously, even though he’s been working in it since 1939, when he started at age 17 as a gofer for Timely Comics. (Within two years, he’s become an editor, art director and head writer.) The comics he creates are so disrespected that he tries to hide his profession when asked about them during cocktails.

In 1961, however, Lee received a directive from Martin Goodman, the publisher of the company that was to be renamed Marvel. He is ordered to design a team of superheroes capable of rivaling DC’s Justice League (which has become the backbone of the so-called Silver Age of Comics). Lee, tired of superheroes, is ready to leave the company. But his wife, English-born beauty Joan Lee, suggests he create the kind of characters he’s always talked about – a more realistic brand of comics, that ordinary people could relate to.

With nothing to lose, he presents the Fantastic Four as a new breed of superheroes: characters with a hint of angst and a host of ordinary problems – they bicker and harbor their anger and anxiety, they worry about things like paying the rent, and in The Thing’s case who have serious self-esteem issues. Comics historian Peter Sanderson has made the brilliant analogy that DC, with the Justice League and the Flash, was like the big Hollywood studios and that the Marvel Comics that Stan Lee invented was like the French New Wave: the coup d’art. sending a reality-based revolution in comics.

And here’s when the tingle comes. Marvel was churning out product, sometimes two comics a day, so there wasn’t much time to indulge in the creative process. Lee, writing the Fantastic Four, would come up with a storyline, which might just be an abstract story concept; he would then turn it over to the illustrator, Jack Kirby, who created panels that furthered the story in his own way. Only after the art is complete will Lee write the words, placing them in speech bubbles. This became known as the Marvel Method.

But what you see in “Stan Lee” is that it was a “method” rooted in the chance of make-up as you go. The stories weren’t planned or meticulously executed; they were essentially improvised. And that, it turns out, was their glory. The stories had a casual existential kick (the New Wave element). Their scruffy human spirit was embodied in the very way they were created. What Lee brought to the equation was a desire to see heroes who were like us, as well as monsters and villains who weren’t so one-dimensional you couldn’t sympathize with them. The Incredible Hulk, launched just after the Fantastic Four, was a character designed in the mind of Boris Karloff in “Frankenstein”: a totemic ghoul of mystery that was strangely close to your heart.

“Stan Lee” is a fan-service documentary released by Disney+ (it comes out June 16), but it’s very well done, and watching it, you’re faced with a revelation: that the comic books Lee started creating in 1961 not only marked a seismic break from the comics of the past. Their prickly, flawed humanity now stands in stark contrast to the majority of comic book movies over the past 40 years.

All of those blockbusters — the movies that not only rolled Hollywood, but remade American culture — are endlessly “relatable,” in the way the heroes ride market-tested aspirational arcs and speak with the cynical yapping that is the language of the American state of entertainment. But Lee’s dream of superheroes who look like us? This lives on much more in the comics than in the movies. And in that sense, every time you’ve seen Stan Lee (who died in 2018) make an appearance in a Marvel movie, he was lending his credit to a form of pop culture that owed him much of its existence but violated, on some level, the spirit he represented.

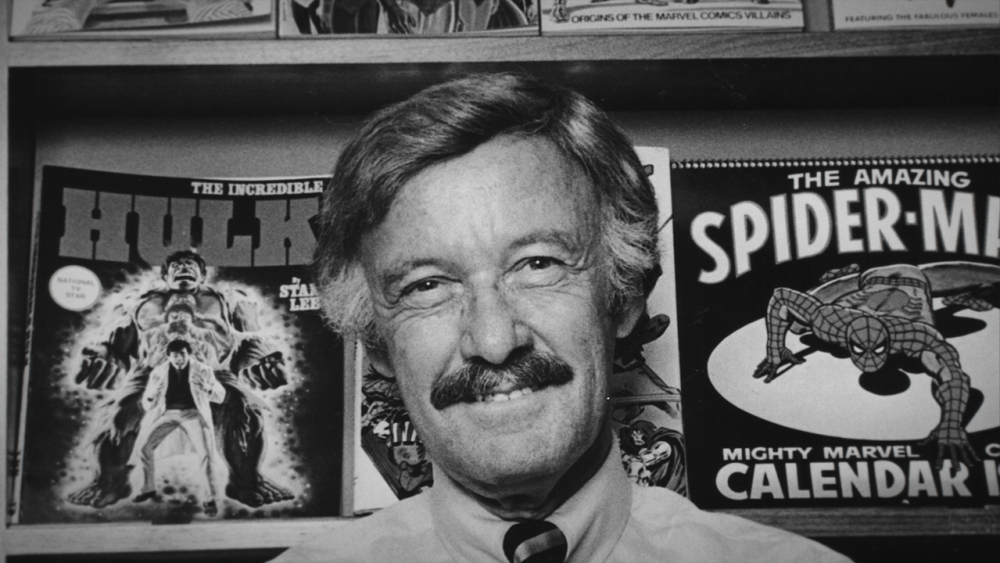

I’m not accusing him of selling himself. Lee, who rose to stardom in the comics world in the ’70s, had every right to rely on the iconic quality that Marvel had achieved. And he was, of course, an exuberant spokesperson. Watching “Stan Lee,” it’s fun to see how his image has evolved. The film opens with a clip of him from what looks like the late ’50s, when he was an important figure but not yet a household name. Without the mustache, and without the streaks and extensions of hair that later in life gave him that weird used-car salesman-icon-of-cool cachet, he comes across as a pretty ordinary guy, like a high school science teacher with a trace of Gene Kelly’s verve.

But as time passes and he begins to speak at conventions that resemble the video versions of Comic-Con, he transforms his image into something tasty. By the time he appears on Tom Snyder’s “Tomorrow Show,” debating with the DC Comics publisher whether comics are just a form of entertainment or something richer and deeper, we can see how Lee embraced his pubic image almost like the alter ego of one of his comic book characters.

He has a heroic moment when he invents Spider-Man. He creates the character from the same impulse he did with the Fantastic Four and the Hulk – the desire to inject the comics with everyday realism. He also describes the creative moment of looking at a fly on the wall and thinking: What if a person could cling to surfaces like that? But when he pitched the concept to Martin Goodman, Marvel’s editor, Goodman said no. So Lee decides to weave Spider-Man’s origin story into the very last issue of Amazing Fantasy – a series that was ending, so it didn’t matter what he put into it. We see panels from this issue, and it’s the whole damn Spider-Man saga, right down to teenage Peter Parker living with an anxiety that neither Tobey Maguire, nor Andrew Garfield, nor Tom Holland came close to summoning. The rest is web history.

David Gelb, director of the delicious “Jiro Dreams of Sushi” (2011), captures something about Stan Lee that seems as real as it is irresistible: that he was the rare creature who grew up happy and stayed that way. Born Stanley Lieber, he was raised in New York during the Depression, the son of Romanian Jewish immigrants, and his father hardly ever held a job. But he used the brutality of his upbringing to lower his expectations. The idea of finding a steady job was about as lofty as his dreams were.

From the moment he became the creative force behind Timely Comics, he was living the dream. Joan was his soulmate and his muse, and the film suggests they had a marriage unmitigated in his devotion. (They remained together until his death, at age 95, in 2017.) But just because Lee followed his happiness and found it, doesn’t mean there wasn’t drama. He created his most legendary comics with two artists, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, and the film shows us what each of these visual wizards brought to the table. Kirby was the show’s maestro, Ditko more of a silent psychodramatic cartoonist – think Spielberg versus Ingmar Bergman. Both were giants. But when it came to claiming credit for the final product, Lee could be silly. We hear Lee and Kirby debate the issue on a radio show in the ’80s, years after they worked together, and it’s clear the rivalry hasn’t diminished. Still, it’s oddly reassuring to hear that stubborn ego streak in Stan Lee. He does something that Lee himself would have appreciated: humanizing the creative superhero of the comic books.