[ad_1]

However, Robrook is also an exception. Koopman led a landmark 17-person study testing whether modulating the electrical signals of the nervous system can reduce inflammation and joint pain in rheumatoid arthritis. According to a 2016 article, Robrook was one of the few who achieved a marked and sustained reduction in disease severity.

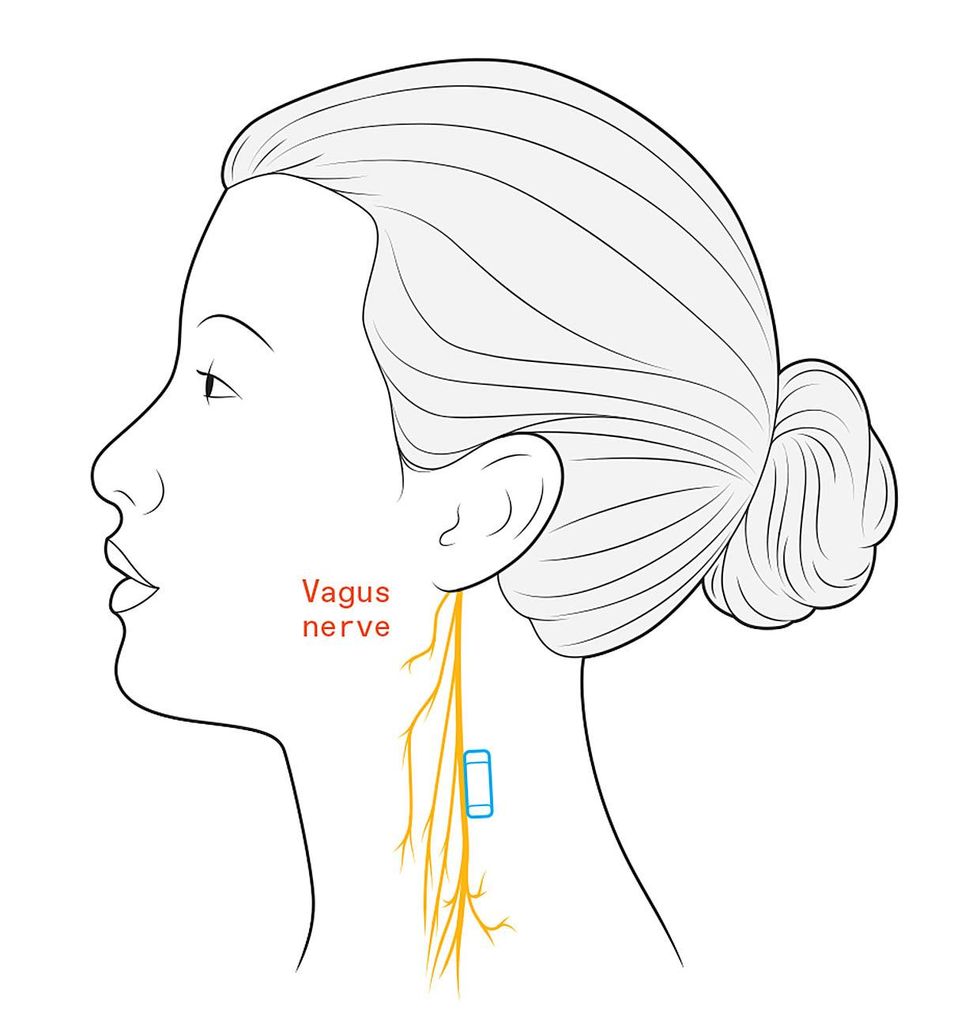

The SetPoint implant is inserted near the patient’s vagus nerve, which runs down from the brain and supplies the spleen and other vital organs.Chris Philpot

The SetPoint implant is inserted near the patient’s vagus nerve, which runs down from the brain and supplies the spleen and other vital organs.Chris Philpot

Pilot studies like Koopman’s are one thing, but scientific validity requires randomized, mock-controlled trials. Physicians, neuroscientists and bioengineers should soon better understand the operation of electroceutical devices. In late 2023, SetPoint Medical, Valencia, Calif., which sponsored Koopman’s original trial, will report preliminary results from Reset-RA, the first large-scale study of nerve stimulation in autoimmune disease. Like the previous trial, the Reset-RA study targets the vagus nerve, the main communication channel between the brain and body, in an attempt to fight inflammation.

Expectations are loaded. Although devices using electrical impulses are already widespread in medicine, all of these platforms are connected to neural circuits that directly affect diseased tissues; for example, deep brain stimulants help with the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease by hacking the control center of the brain’s movement. No one pays attention to what Kevin Tracy, in an influential 2002 paper, called the “inflammatory reflex,” a neural network that indirectly regulates immune responses to infection and injury via the vagus nerve and its associated organs.

Tracy, a former neurosurgeon who heads the Institute for Medical Research. Feinstein in Manhasset, New York, was the first to show that stimulation of the vagus nerve in rats can suppress the release of immune signaling molecules. He later attributed this effect to vagus nerve signals to the spleen, a fist-sized organ in the abdomen where immune cells are activated. In 2007, Tracy co-founded SetPoint to bring treatment to the clinic.

First, the company repurposed an off-the-shelf implant used to control seizures in people with epilepsy. SetPoint optimized stimulation parameters based on rodent research before delivering devices to patients like Robrook. She and other recipients had a cookie-sized pulse generator surgically inserted into their chests. The wire snaked up the left side of the neck, where the electrode wrapped around the vagus nerve. It gave a gentle, 1 minute burst of stimulation up to four times a day.

The research targets the vagus nerve, the main communication channel between the brain and body, in an attempt to fight inflammation.

Paul Peter Tuck, an immunologist and biotech entrepreneur who co-led the study with Koopman, was concerned that patients with rheumatoid arthritis might not want to undergo surgery and have hardware implanted under the skin. But after the study was published on Dutch television, Tuck was inundated with requests from patients sick of endless pill and injection regimens. “It was my unplanned market research,” says Tuck. “To my surprise, there are many patients who would prefer a single operation.”

While the results of the study were promising, the device itself was unwieldy. So SetPoint redesigned the platform, downsizing it to a peanut-sized neurostimulator with built-in electrodes and a wirelessly rechargeable battery encapsulated in a silicone holding capsule just above the vagus nerve in the neck. “It’s like going from an old car to a Tesla — it’s completely redesigned,” says SetPoint chief medical officer David Chernoff.

A small test conducted in 2018 showed that this miniature device is safe. The 250-person Reset-RA study, in which half of the participants do not receive stimulation during the first 12 weeks after implantation, is currently evaluating efficacy. If that works, trials for other autoimmune diseases could follow.

SetPoint has reduced the size of the vagus nerve stimulator so that it can be implanted in the patient’s neck instead of the chest.Setpoint Medical

SetPoint has reduced the size of the vagus nerve stimulator so that it can be implanted in the patient’s neck instead of the chest.Setpoint Medical

Meanwhile, other companies are testing devices that target nerves closer to the site of immune activation “from a business standpoint,” says Christoffer Famm, president of UK-based Galvani Bioelectronics. Famm argues that this target organ-based approach to nerve injury should provide more precise, disease-specific neuromodulation without the off-target effects of vagus nerve shock, which plays a central role in many bodily processes.

A joint venture between Google parent company Alphabet and British pharmaceutical company GSK Galvani is currently evaluating its implantable splenic nerve stimulator in a small number of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Minneapolis-headquartered SecondWave Systems is also testing whether ultrasonic waves directed at the spleen can have the same immune-suppressing effect without the burden of invasive surgery. Both Galvani and SecondWave plan to announce the first human data within the next year.

“Neuromodulation definitely makes a difference,” says Gene Civillico, a neurotechnologist at Northeastern University in Boston who previously led bioelectronics research at the US National Institutes of Health. “Controlling neural tissue with precision in space and time will help us cure or reverse many disease states,” Civilico says. SetPoint and other companies hope to prove him right next year.

This article appeared in the January 2023 print issue titled Arthritis Gets a Boost.

From articles on your site

Related articles online